- Home

- Psychologist & Psychiatrist C&P Examiners

- Disability Exams Research Archives

Disability Exams Research Archives

Archived posts from the Disability Exams Research page.

PTSDexams.net is an educational site with no advertising and no affiliate links. Dr. Worthen conducts Independent Psychological Exams (IPE) with veterans, but that information is on his professional practice website.

Life Events Checklist (LEC): Reliable & Valid Scoring Methods

Citation

Weis, Carissa N., E. Kate Webb, Sarah K. Stevens, Christine L. Larson, and Terri A. deRoon-Cassini. “Scoring the Life Events Checklist: Comparison of Three Scoring Methods.” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. Published ahead of print, 24 June 2021. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001049

Abstract

Objective: Prior trauma history is a reliable and robust risk predictor for PTSD development. Obtaining an accurate measurement of prior trauma history is critical in research of trauma-related outcomes.

The Life Events Checklist (LEC) is a widely used self-report measure of trauma history that categorizes events by the proximity to trauma exposure; however, the field has published multiple scoring methods when assessing the LEC.

Herein, we propose a novel scoring procedure in which total scores from the LEC are weighted according to the proximity of trauma exposure with “experienced” events weighted most and “learned about” events weighted least.

Method: The utility of this weighted score was assessed in two traumatically-injured civilian samples and compared against previously published scoring methods, including a nonweighted score including all events experienced, witnessed, and learned about, as well as a score consisting of only experienced events.

Results: Results indicated the standard total score was most reliable, followed by the weighted score. The experienced events score was least reliable, but the best predictor of future PTSD symptoms.

Conclusions: One method to balance the predictive strength of experienced events and the excellent reliability of a total LEC score, is to adopt the newly proposed weighted score.

Future use of this weighted scoring method can provide a comprehensive estimate of lifetime trauma exposure while still emphasizing the direct proximity of experienced events compared with other degrees of exposure.

Clinical Impact Statement

The Life Events Checklist (LEC) is a widely used self-report measure of trauma history that categorizes events by the proximity of trauma exposure; however, the field has published multiple scoring methods for the LEC.

We proposed a novel scoring procedure in which total scores are weighted according to the proximity of trauma exposure with “experienced” events weighted most and “learned about” events weighted least.

Results assessed in two traumatically injured civilian samples indicated the weighted score is reliable and valid.

Future utilization of this scoring method will provide a comprehensive estimate of lifetime trauma while emphasizing proximity of trauma exposure.

Implications for C&P Examiners

C&P psychologists and psychiatrists usually do not score the LEC, if they even use the instrument. [Note that the precise name is: Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5).]ß

C&P examiners generally use the LEC to identify index traumas, which serve as the basis for symptom inquiry on the CAPS-5, Last Month Version.Φ

(Keep in mind that, for PTSD exams, the VA needs to know if a veteran currently suffers from the disorder, not if they ever suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder.)

But if you wish to ascertain the overall "trauma load", or "trauma burden", experienced by an examinee or patient, understanding LEC scoring methods should prove useful.

Thus, to understand a person's trauma burden, you could administer the LEC-5, compute the Weighted Score, and then administer the CAPS-5, Lifetime Version.

Footnotes

ß. Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5), https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/te-measures/life_events_checklist.asp

Φ. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5).

Detecting Feigned TBI Using Pupillometry

Citation

Patrick, Sarah D., Lisa J. Rapport, Robert J. Kanser, Robin A. Hanks, and Jesse R. Bashem. “Detecting Simulated versus Bona Fide Traumatic Brain Injury Using Pupillometry.” Neuropsychology, published ahead of print, 20 May 2021.

Abstract

Objective: Pupil dilation patterns are outside of conscious control and provide information regarding neuropsychological processes related to deception, cognitive effort, and familiarity.

This study examined the incremental utility of pupillometry on the Test of Memory Malingering (TOMM) in classifying individuals with verified traumatic brain injury (TBI), individuals simulating TBI, and healthy comparisons.

Method: Participants were 177 adults across three groups: verified TBI (n = 53), feigned cognitive impairment due to TBI (SIM, n = 52), and heathy comparisons (HC, n = 72).

Results: Logistic regression and ROC curve analyses identified several pupil indices that discriminated the groups.

Pupillometry discriminated best for the comparison of greatest clinical interest, verified TBI versus simulators, adding information beyond traditional accuracy scores.

Simulators showed evidence of greater cognitive load than both groups instructed to perform at their best ability (HC and TBI).

Additionally, the typically robust phenomenon of dilating to familiar stimuli was relatively diminished among TBI simulators compared to TBI and HC. This finding may reflect competing, interfering effects of cognitive effort that are frequently observed in pupillary reactivity during deception. However, the familiarity effect appeared on nearly half the trials for SIM participants.

Among those trials evidencing the familiarity response, selection of the unfamiliar stimulus (i.e., dilation-response inconsistency) was associated with a sizable increase in likelihood of being a simulator.

Conclusions: Taken together, these findings provide strong support for multimethod assessment: adding unique performance assessments such as biometrics to standard accuracy scores.

Continued study of pupillometry will enhance the identification of simulators who are not detected by traditional performance validity test scoring metrics.

(emphasis & line breaks added to ease online reading)

Impact Statement

Question: Is pupillometry a useful biometric measure for identifying feigned cognitive impairment?

Findings: Several pupillary indices discriminated feigned impairment from healthy adults and adults with TBI instructed to perform their best, both as independent indicators and beyond traditional TOMM accuracy scores [incremental utility].

Importance: The findings support the utility of biometric measures, such as pupillometry, in the context of performance validity assessment.

Next Steps: The examination of pupillometry may enhance the detection of individuals feigning cognitive impairment who are not identified by traditional performance validity tests.

Normal Cognitive Test Scores Cannot Be Interpreted as Accurate with Failed PVT

Citation

Martinez, Karen A., Courtney Sayers, Charles Hayes, Phillip K. Martin, C. Brendan Clark, and Ryan W. Schroeder. “Normal Cognitive Test Scores Cannot Be Interpreted as Accurate Measures of Ability in the Context of Failed Performance Validity Testing: A Symptom- and Detection-Coached Simulation Study.” Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. Published ahead of print, 16 May 2021.

Abstract

Introduction: While use of performance validity tests (PVTs) has become a standard of practice in neuropsychology, there are differing opinions regarding whether to interpret cognitive test data when standard scores fall within normal limits despite PVTs being failed.

This study is the first to empirically determine whether normal cognitive test scores underrepresent functioning when PVTs are failed.

Method: Participants, randomly assigned to either a simulated malingering group (n = 50) instructed to mildly suppress test performances or a best-effort/control group (n = 50), completed neuropsychological tests which included the North American Adult Reading Test (NAART), California Verbal Learning Test – 2nd Edition (CVLT-II), and Test of Memory Malingering (TOMM).

Results: Groups were not significantly different in age, sex, education, or NAART predicted intellectual ability, but simulators performed significantly worse than controls on the TOMM, CVLT-II Forced Choice Recognition, and CVLT-II Short Delay Free Recall.

The groups did not significantly differ on other examined CVLT-II measures. Of simulators who failed validity testing, 36% scored no worse than average and 73% scored no worse than low average on any of the examined CVLT-II indices.

Conclusions: Of simulated malingerers who failed validity testing, nearly three-fourths were able to produce cognitive test scores that were within normal limits, which indicates that normal cognitive performances cannot be interpreted as accurately reflecting an individual’s capabilities when obtained in the presence of validity test failure.

At the same time, only 2 of 50 simulators were successful in passing validity testing while scoring within an impaired range on cognitive testing. This latter finding indicates that successfully feigning cognitive deficits is difficult when PVTs are utilized within the examination.

(emphasis & line breaks added to ease online reading)

PTSD: Comorbid Mental Disorders, Chronic Pain, and Medical Conditions

"Common comorbidities significantly influence disability associated with PTSD, often more strongly than PTSD symptoms."

- Citation

- Abstract

Citation

Manhapra, Ajay, Elina A. Stefanovics, Taeho Greg Rhee, and Robert A. Rosenheck. “Association of Symptom Severity, Pain and Other Behavioral and Medical Comorbidities with Diverse Measures of Functioning among Adults with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 134 (Feb 2021): 113–20.

Abstract

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an often disabling mental disorder whose management typically focuses on reducing PTSD symptoms. Chronic pain and other comorbidities that commonly accompany PTSD symptoms may also be independently associated with disability.

Using data from the 2012-2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, we examined the independent association of PTSD symptom severity, pain interference, non-PTSD psychiatric and substance use disorders (SUD), and medical illnesses with each of four domains of function:

- mental health-related quality of life as measured by the Mental Health Composite Score (MCS) of the Short Form-12;

- physical functioning assessed with the Physical Function Score (PFS) of the Short Form-12;

- perceived social support from the Interpersonal Support and Evaluation List-12 (ISEL-12); and

- self-reported past year employment.

Among 1779 individuals representing 11 million U.S. adults who met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-5 (DSM-5) criteria for Past Year PTSD, the MCS (41.2; SD 12.5), PFS (44.8; SD 13.2) and ISEL-12 (33.6; SD 7.2) indicated substantial disability when compared to population norms, and only 63.6% were employed.

Multiple regression showed the MCS had a modest negative association with PTSD symptoms, pain interference, psychiatric multimorbidity and medical comorbidity although not with SUD. PFS and employment had significant negative associations with pain interference and medical comorbidity. ISEL-12 had a weak negative association with PTSD symptoms and non-PTSD psychiatric comorbidity.

Common comorbidities thus significantly influence disability associated with PTSD, often more strongly than PTSD symptoms. PTSD treatment may require integrative multimorbidity management beyond a focus on PTSD symptoms.

[emphasis and line breaks added to ease online reading; light editing to the list of four domains]

Implications for C&P Examiners

- (a) If you examine a veteran for an Initial (original) PTSD exam, and if you believe he/she/they suffers from service-related PTSD; or

(b) If you examine a veteran for a Review PTSD exam, then ... - Determine if the veteran suffers from other mental disorders, medical conditions, or chronic pain, and then ...

- Determine if any comorbid conditions you identify are (or might be) proximately due to or the result of PTSD, i.e., secondary disorders or conditions.†

If you do not have time to do #2 and #3 (above), consider adding a sentence or two raising the possibility of secondary conditions. Note that such a statement is not required, and some would argue it is not appropriate.

If you conduct a Review PTSD exam, and you determine that one or more comorbid psychiatric, medical, or chronic pain disorders are secondary to PTSD, but the veteran did not file a secondary condition claim, consider either

(i) writing an Opinion and Rationale about the secondary conditions anyway; or

(ii) include a sentence or two indicating the possibility of PTSD-related secondary conditions.

I almost always choose the first option (i) because it saves everyone time and is consistent with fundamental principles of the U.S. veterans disability benefits program.α,β

At the same time, there are legitimate arguments for not providing an expert witness opinion when the referring agency did not request such an opinion.

Footnotes

†. Disabilities that are proximately due to, or aggravated by, service-connected disease or injury, 38 C.F.R. § 3.310.

α. Gilbert v. Derwinski, 1 Vet. App. 49, 54 (1990) (“… when a veteran seeks benefits and the evidence is in relative equipoise, the law dictates that veteran prevails. This unique standard of proof is in keeping with the high esteem in which our nation holds those who have served in the Armed Services. It is in recognition of our debt to our veterans that society has through legislation taken upon itself the risk of error …”).

β. Hodge v. West, 155 F.3d 1356, 1362 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (“... the character of the veterans’ benefits statutes is strongly and uniquely pro-claimant.”).

MST Associated with Poor Sexual Functioning & Decreased Satisfaction Among Female Veterans

- Citation

- Abstract

- Trauma Symptom Inventory-2 (TSI-2)

- Related Article

Citation

K. Blais, Rebecca, Alyson K. Zalta, and Whitney S. Livingston. “Interpersonal Trauma and Sexual Function and Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Negative Affect Among Survivors of Military Sexual Trauma.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Published online ahead of print, 29 Sep 2020, https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520957693

Abstract

Healthy sexual function among women service members/veterans (SM/Vs) is associated with higher quality of life, lower incidence and severity of mental health diagnoses, higher relationship satisfaction, and less frequent suicidal ideation.

Although trauma exposure has been established as a predictor of poor sexual function and satisfaction in women SM/Vs, no study to date has examined whether specific trauma types, such as military sexual trauma (MST), increase risk for sexual issues. Moreover, the possible mechanisms of this association have not been explored.

The current study examined whether posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression symptom clusters mediated the association of trauma type and sexual function and satisfaction in 426 trauma-exposed women SM/Vs.

Two hundred seventy participants (63.4%) identified MST as their index trauma. Path analyses demonstrated that MST was related to poorer sexual function and lower satisfaction relative to the other traumas (χ2[28, N = 426] = 43.3, p = 0.03, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 0.99, and RMSEA = 0.04), and this association was mediated by higher non-somatic depressive symptoms and PTSD symptom clusters of anhedonia and negative alterations in cognition and mood (NACM).

Causality cannot be inferred due to the cross-sectional nature of the data. However, our findings suggest that interventions aimed at decreasing sexual issues among female SM/Vs with MST should target depressogenic symptoms, whether the origin is depression or PTSD. Longitudinal research exploring the etiological processes that contribute to sexual dysfunction among those with MST is needed.

Implications for C&P Examiners

Although, as the authors emphasize, one cannot infer causality with cross-sectional research, this study adds to a body of research demonstrating that sexual assault, abuse, etc., including MST, is strongly associated with, and is likely a primary cause of subsequent sexual dysfunction and decreased sexual satisfaction.

Thus, sexual dysfunction and decreased sexual satisfaction would seem to constitute empirically-grounded "behavioral markers" for MST-related C&P exams.

Trauma Symptom Inventory-2 (TSI-2)

The Trauma Symptom Inventory-2 (TSI-2), a reliable and valid broadband psychological inventory, measures trauma-related sexual problems. See the Sexual Disturbance scale and two constituent subscales, Sexual Concerns and Dysfunctional Sexual Behavior.

Related Article

Pulverman, Carey S., and Suzannah K. Creech. “The Impact of Sexual Trauma on the Sexual Health of Women Veterans: A Comprehensive Review.” Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. Published online before print. 22 Aug 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019870912

MMPI-2: Detecting Feigned PTSD

- Citation

- Abstract

- Selected quotes

Citation

Nijdam-Jones, Alicia, Yanru Chen, and Barry Rosenfeld. “Detection of Feigned Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2).” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 12, no. 7 (2020): 790–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000593

Abstract

Objective: This study synthesized the results of 22 studies (N = 3,912) of feigned posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms that used the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2).

Method: Robust variance estimation was used to analyze variables that affected the accuracy of scales used to detect feigned symptoms.

Results: The FB scale (g = 1.60), the Obvious–Subtle scale (g= 1.57), and the Gough Dissimulation Index (F-K; g = 1.56) produced very large effect sizes after controlling for study design. Large and significant effect sizes were also observed for the F scale (g = 1.46), the Fp scale (g = 1.43), and the Ds scale (g = 1.39).

Conclusions: The findings of this study suggest that the MMPI-2 validity scales are useful for identifying individuals who are exaggerating or fabricating psychological symptoms. However, there were differences across validity scales and study designs, with some scales demonstrating stronger performances than others.

Clinical Impact Statement: This study examined the utility of the MMPI-2, a self-report measure of psychopathology and personality functioning, to detect feigned symptoms of PTSD. The findings suggest that the MMPI-2 contains multiple validity scales and indices that are relevant to detecting feigned PTSD. However, mental health professionals should exercise caution when making determinations about feigning based on seemingly elevated scores on the subscales that are most commonly used by professionals.

Selected quotes from article ...

Clinicians should be cautious, particularly when interpreting equivocal test results that might reflect genuine, albeit severe, PTSD symptoms, because elevated scores on these validity scales appear to be common. [p. 795]

---

... an understudied area of research is the impact of developmental trauma, such as childhood abuse, on validity scales. Although childhood sexual abuse and dissociation are associated with higher F scores, the impact of developmental traumas could not be examined in this meta-analysis due to the low number of studies that reported this variable.

Because developmental trauma and adverse childhood experiences could have important implications in forensic and clinical contexts, more research is needed to better understand how these adverse childhood experiences may affect the endorsement of trauma-related items on validity scales. [p. 795–796]

---

As expected, simulation studies generated significantly higher mean scores on the validity scales and larger effect sizes when compared to control samples (particularly using nonclinical control groups) than the other research designs.

This is consistent with Green and Rosenfeld’s (2011) conclusion that simulation studies typically generate stronger classification accuracy than studies with other research designs.

Simulation research designs pose several problems with regard to ecological validity by presenting unrealistic contexts and minimal incentives for feigning. [p. 796]

---

This study found that many of the MMPI-2 validity scales are similar in their utility in differentiating genuine from nongenuine responders. However, the FB scale, the O-S scale, and the F-K index had the largest effect sizes in detecting the difference between genuine or nonclinical control samples and those feigning PTSD.

Mental health professionals may want to consider these indices when assessing for feigned PTSD, and caution should be exercised when making determinations about feigning based on seemingly elevated scores on those subscales that are used most commonly (e.g., F, FP, FBS). [p. 796]

Implications for C&P Examiners

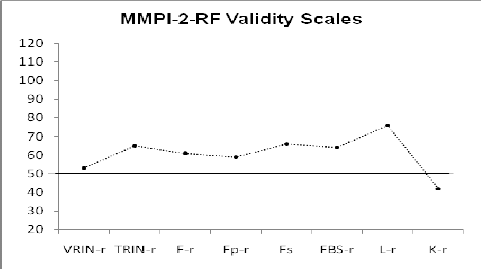

* Remember that veterans with genuine PTSD produce high validity scale scores—two to three three standard deviations above the mean. Therefore, you should not use standard interpretive guidelines for F, FB, Fp, and FBS.

> See the following article for MMPI-2 validity scale score interpretation guidelines for veterans undergoing a PTSD exam for VA disability compensation purposes:

Worthen, Mark D., and Robert G. Moering. “A Practical Guide to Conducting VA Compensation and Pension Exams for PTSD and Other Mental Disorders.” Psychological Injury and Law 4, no. 3 (December 2011): 187–216. [no-cost PDF]

* The Pearson MMPI-2 score reports do not provide scores for the O-S and Ds scales. Given the clinical utility of these two validity scales it might be worth scoring them by hand.

* This study did not evaluate the clinical utility of the Meyers Index (because other researchers have not conducted a lot of research on the Meyers Index).

This is the original study on the Meyers Index:

Meyers, John E., Scott R. Millis, and Kurt Volkert. “A Validity Index for the MMPI-2.” Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 17, no. 2 (February 2002): 157–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/17.2.157 [Open Access]

* Although the MMPI-2-RF has become more popular than the MMPI-2, in part because it does not take as long to complete, the MMPI-2 might be the most effective instrument for a full understanding of a respondent's personality functioning because of the extensive research on MMPI-2 codetypes. (This is a debatable point.)

Some federal agencies, although not the VA, require the MMPI-2. See:

Off. Aerospace Med., Fed. Aviation Admin., Selecting the MMPI-2 versus the MMPI-3, Washington, D.C. (Nov. 18, 2020). [free PDF]

Long-term PTSD Course Among OEF & OIF Veterans

- Citation

- Abstract

Citation

Lee, Daniel J., Lewina O. Lee, Michelle J. Bovin, Samantha J. Moshier, Sunny J. Dutra, Sarah E. Kleiman, Raymond C. Rosen, Jennifer J. Vasterling, Terence M. Keane, and Brian P. Marx. “The 20-Year Course of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms among Veterans.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology 129, no. 6 (2020): 658–69. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32478530/

Abstract

Although numerous longitudinal studies have examined heterogeneity in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom course, the long-term course of the disorder remains poorly understood.

This study sought to understand and predict long-term PTSD symptom course among a nationwide sample of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom veterans enrolled in Veterans Health Administration services.

We assessed PTSD symptoms at 4 time points over approximately 4.5 years (M = 55.11 months, SD = 6.89).

Participants (N = 1,353) with and without probable PTSD were sampled at a 3:1 ratio, and male and female veterans were sampled at a 1:1 ratio to fully explore the heterogeneity of PTSD symptom course and the effect of sex on symptom course.

By coding time as years since index trauma, we estimated the course of PTSD symptoms over 20 years.

Results indicate symptom course is most appropriately characterized by substantial heterogeneity.

On average, veterans experienced initial PTSD symptom severity above the diagnostic threshold following trauma exposure, which was initially stable over time and later began to gradually improve.

Although results indicate symptoms eventually began to decline, this effect was gradual; most participants continued to meet or exceed the PTSD provisional diagnostic threshold long after trauma exposure.

We identified several predictors and correlates of symptom course, including Hispanic ethnicity, postdeployment social support, and co-occurring psychopathology.

Results highlight the heterogeneous nature of PTSD symptom course following trauma exposure and the urgency of the need to ensure access to evidence-based care and to improve available treatments.

[emphasis and line breaks added to ease online reading]

Implications for C&P Examiners

(1) When veterans file a claim for an increased disability rating, keep in mind that, in general, PTSD symptoms very gradually subside, but remain above the threshold for a PTSD diagnosis. Thus, increasingly worse symptoms over time goes against the general trend.

Of course, this does not mean that any veteran who files a claim for an increased disability rating is feigning.

It simply means that an examiner should consider other reasons for such a claim such as (from the veteran's perspective) a belief that if other veterans, whose traumas were less severe, have a 70% or 100% disability rating for PTSD, then my rating should be at least as high.

In my estimation, such reasoning might not be correct, in terms of the purpose of veterans disability benefits, but it is understandable.

(2) Alcohol abuse (Alcohol Use Disorder) exacerbates PTSD such that symptomatology and associated functional impairment worsen over time.

Effect of Receiving Disability Compensation

From the article:

We collected electronic medical record information regarding VA service-connected PTSD disability status (receiving benefits, compensation, or both vs. not) at T1 [Time 1] for all participants. [p. 660]

... VA service-connected disability for PTSD at T1 [was] significantly associated with greater PTSD symptom severity at each time point. [p. 664]

... Regarding the observed association between service-connected PTSD disability status and symptom course, the most parsimonious explanation is that those with the more severe symptoms are more likely to have greater associated impairment and thus more likely to be receiving compensation and other benefits for their PTSD-related disability.

Because we do not have detailed information about the extent and type of PTSD treatment received by participants or response bias, we were unable to examine longstanding concerns that receiving PTSD-related disability compensation and other benefits may disincentivize treatment seeking or acknowledgment of symptom improvement (McNally & Frueh, 2013). [p. 666]

Military Sexual Assault Worse Than Civilian Sexual Assault for Women

All Sexual Assault Causes Substantial Harm

Citation

Newins, Amie R., Jeffrey J. Glenn, Laura C. Wilson, Sarah M. Wilson, Nathan A. Kimbrel, Jean C. Beckham, Patrick S. Calhoun, and VA Mid-Atlantic MIRECC Workgroup. "Psychological Outcomes Following Sexual Assault: Differences by Sexual Assault Setting." Psychological Services. ePub ahead of print, 9 Apr 2020. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000426

Abstract

Sexual assault is associated with increased psychological distress. It is possible that military sexual assault (MSA) is associated with heightened psychological distress compared to adult sexual assault that occurs pre- or postmilitary service due to the nature of the military setting.

Veterans and service members (N = 3,114; 19.6% women) who participated in the Post-Deployment Mental Health Study completed self-report measures of sexual assault history, symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), symptoms of depression, hazardous alcohol use, drug use, and suicidal ideation.

Women who reported a history of MSA endorsed higher levels of all types of psychological distress than women who did not experience adult sexual assault. Women who reported a history of MSA also endorsed higher levels of PTSD and depression symptoms than women who experienced pre- or postmilitary adult sexual assault.

Men who reported a history of adult sexual assault, regardless of setting, reported higher levels of PTSD and depression symptoms than individuals who did not experience adult sexual assault.

MSA [military sexual assault] was associated with higher psychological distress than pre- or postmilitary adult sexual assault among women.

Among men, distress associated with MSA was comparable to sexual assault outside the military.

Women may face unique challenges when they experience sexual assault in the military, and men may face additional stigma (compared to women) when they experience sexual assault, regardless of setting.

Impact Statement: The results revealed that sexual assault that occurred during military service had a greater impact on mental health outcomes compared to sexual assault that occurred pre- or postmilitary service for women.

In contrast, the impact of sexual assault on mental health symptoms did not vary by setting for men.

Clinicians who work with veterans should assess for factors unique to the military setting that may have increased the impact of MSA for women and for factors unique to men that may influence mental health outcomes following any sexual assault.

Implications for C&P Examiners

Even if a female service member or veteran suffered pre-military sexual trauma, this research suggests that military sexual assault likely aggravated adverse psychological sequelae of pre-military trauma since, in general, in-service sexual assault leads to even worse mental health outcomes.

For male survivors of military sexual assault, examiners should be familiar with the literature on male sexual assault survivors generally, MST survivors in particular, and on potential implicit biases you might have about male sexual assault survivors, especially if you are male. For example:

Male Rape Myths

(a) "Being raped by a male attacker is synonymous with the loss of masculinity"

(b) “men who are sexually assaulted by men must be gay”

(c) “men are incapable of functioning sexually unless they are sexually aroused”

(d) “men cannot be forced to have sex against their will”

(e) “men are less affected by sexual assault than women”

(f) “men are in a constant state of readiness to accept any sexual opportunity” (especially with female perpetrator)

(g) “a man is expected to be able to defend himself against sexual assault” (especially with male perpetrator)

SOURCE: Chapleau, Kristine M., Debra L. Oswald, and Brenda L. Russell. "Male Rape Myths: The Role of Gender, Violence, and Sexism." Journal of Interpersonal Violence 23, no. 5 (2008): 600-615.

AACN 2021 Consensus Statement on Neuropsychological Assessment of Effort, Response Bias, and Malingering

Citation

Sweet, Jerry J., Robert L. Heilbronner, Joel E. Morgan, Glenn J. Larrabee, Martin L. Rohling, Kyle B. Boone, Michael W. Kirkwood, Ryan W. Schroeder, Julie A. Suhr, and Conference Participants. “American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology (AACN) 2021 Consensus Statement on Validity Assessment: Update of the 2009 AACN Consensus Conference Statement on Neuropsychological Assessment of Effort, Response Bias, and Malingering.” Clinical Neuropsychologist, epub before print (6 April 2021): 1–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2021.1896036

Abstract

Objective: Citation and download data pertaining to the 2009 AACN consensus statement on validity assessment indicated that the topic maintained high interest in subsequent years, during which key terminology evolved and relevant empirical research proliferated.

With a general goal of providing current guidance to the clinical neuropsychology community regarding this important topic, the specific update goals were to:

- identify current key definitions of terms relevant to validity assessment;

- learn what experts believe should be reaffirmed from the original consensus paper, as well as new consensus points; and

- incorporate the latest recommendations regarding the use of validity testing, as well as current application of the term ‘malingering.’

Methods: In the spring of 2019, four of the original 2009 work group chairs and additional experts for each work group were impaneled. A total of 20 individuals shared ideas and writing drafts until reaching consensus on January 21, 2021.

Results: Consensus was reached regarding affirmation of prior salient points that continue to garner clinical and scientific support, as well as creation of new points.

The resulting consensus statement addresses:

- definitions and differential diagnosis,

- performance and symptom validity assessment, and

- research design and statistical issues.

Conclusions/Importance: In order to provide bases for diagnoses and interpretations, the current consensus is that all clinical and forensic evaluations must proactively address the degree to which results of neuropsychological and psychological testing are valid.

There is a strong and continually-growing evidence-based literature on which practitioners can confidently base their judgments regarding the selection and interpretation of validity measures.

(emphasis and line breaks added to ease online reading)

Psychological Injury and Law 13, No. 4 → Packed with Superb Articles

I don't think I've ever recommended an entire issue of a journal before. But this publication contains so many excellent articles that I must recommend the entire December 2020 issue of Psychological Injury and Law.

I posted the citations and abstracts for the articles below. Leading scholars in forensic psychology—such as William E. Foote, Jane Goodman-Delahunty, Eileen A. Kohutis, and Gerald Young, to name just a few—penned many of the articles.

If you do not have easy access to journals, here are a couple of options:

- If you are a VIP Member (free), I include detailed strategies for obtaining journal articles in the VIP Member edition of the Recommended Reading List for Psych C&P Examiners, which is located on the VIP members download page (password required).

Citation

Fokas, Kathryn F., and Julie M. Brovko. “Assessing Symptom Validity in Psychological Injury Evaluations Using the MMPI-2-RF and the PAI: An Updated Review.” Psychological Injury and Law 13, no. 4 (December 2020): 370–82.

Abstract

Among the most pressing considerations in psychological injury litigation is potential overreporting of symptoms or impairments by the plaintiff.

It is thus imperative for psychological injury evaluators to possess a working understanding of the conceptual and empirical foundations of symptom validity tests (SVTs).

This literature review first covers foundational knowledge to guide evaluators in the careful interpretation of SVTs.

It then focuses on two of the most well-established SVTs, i.e., the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2-Restructured Form (MMPI-2-RF) and the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI). Each instrument is reviewed for its overreporting scales, including scale development strategies, standard cutoff values, and research support, with particular attention afforded to psychological injury litigation considerations.

Findings from this narrative review suggest that both the MMPI-2-RF and the PAI are sound SVTs with growing bodies of empirical support. However, they must be interpreted with special caution in the unique context of psychological injury evaluations, where there runs a greater risk of false-positive identification of overreporting.

The strengths of each measure are contrasted, revealing general themes. Notably, the MMPI-2-RF excels in its accumulation of research support and civil litigant-specific norms, whereas the PAI leads SVT research in innovation and advanced detection techniques.

Both measures are better equipped to detect feigned psychopathology than cognitive or medical impairments. Recommendations for forensic evaluators and areas for future research are presented accordingly.

(emphasis and line breaks added to ease online reading)

Citation

Foote, William E., Jane Goodman-Delahunty, and Gerald Young. “Civil Forensic Evaluation in Psychological Injury and Law: Legal, Professional, and Ethical Considerations.” Psychological Injury and Law 13, no. 4 (December 2020): 327–53.

Abstract

Psychologists who work as therapists or administrators, or who engage in forensic practice in criminal justice settings, find it daunting to transition into practice in civil cases involving personal injury, namely psychological injury from the psychological perspective.

In civil cases, psychological injury arises from allegedly deliberate or negligent acts of the defendant(s) that the plaintiff contends caused psychological conditions to appear.

These alleged acts are disputed in courts and other tribunals. Conditions considered in psychological injury cases include posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, chronic pain conditions, and sequelae of traumatic brain injury.

This article outlines a detailed case sequence from referral through the end of expert testimony to guide the practitioner to work effectively in this field of practice. It addresses the rules and regulations that govern admissibility of expert evidence in court.

The article provides ethical and professional guidance throughout, including best practices in assessment and testing, and emphasizes evidence-based forensic practice.

(emphasis and line breaks added to ease online reading)

Citation

Kerig, Patricia K., Michaela M. Mozley, and Lucybel Mendez. “Forensic Assessment of PTSD Via DSM-5 Versus ICD-11 Criteria: Implications for Current Practice and Future Research.” Psychological Injury and Law 13, no. 4 (December 2020): 383–411.

Abstract

Recognition of the high prevalence of trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress symptoms among adult and youth offenders has inspired calls for justice systems to engage in trauma-informed practices, particularly with regard to the assessment of trauma histories and posttraumatic reactions in legal contexts.

Accordingly, skills in trauma assessment have become essential professional competencies for those conducting psychological evaluations in the justice system.

However, there are a number of challenges to effective practice, including:

- the existence of two distinctly different sets of diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the DSM-5 versus ICD-11;

- controversies over whether separate diagnostic entities comprising complex PTSD and developmental trauma disorder are valid;

- limitations of the existing measures for assessing and diagnosing the disorder(s);

- difficulties with differential diagnosis of overlapping disorders and detection of malingering; and

- limited attention to cultural, ethnic, and racial diversity in the idioms and expressions of posttraumatic stress reactions.

The present article reviews these challenges and offers recommendations for future research and clinical practice.

(emphasis and line breaks added to ease online reading)

Citation

Kohutis, Eileen A., and Shawn McCall. “The Eggshell and Crumbling Skull Plaintiff: Psychological and Legal Considerations for Assessment.” Psychological Injury and Law 13, no. 4 (December 2020): 354–69.

Abstract

Forensic psychologists are called to assist judges and juries to understand the nature and extent of how particular psychological injuries manifest themselves for individual victims and how injuries impact the victims’ lives.

In order to be most helpful, psychologists need to understand the legal frameworks, concepts, and rules by which tort claims are made and compensated.

The psychologist’s work is particularly difficult and useful—when there is an interaction between old and new injuries and conditions, which invokes the legal concepts of eggshell skull, crumbling skull, and eggshell psyche.

his article first provides a primer of the relevant legal concepts about which the forensic psychologist must be aware so that psychological data, observations, and interpretations may be presented in a way that is familiar and accessible to the legal audience.

The article then proceeds to provide an evaluative framework to approach the difficult task of describing psychological injuries and explaining if and how new and old injuries and conditions effect the victim’s life and functioning.

In particular, the article discusses somatic symptom disorders, factitious disorders, and malingering.

(emphasis and line breaks added to ease online reading)

Citation

Mailis, Angela, Perry S. Tepperman, and Eleni G. Hapidou. “Chronic Pain: Evolution of Clinical Definitions and Implications for Practice.” Psychological Injury and Law 13, no. 4 (December 2020): 412–26.

Abstract

Numerous definitions of pain have been proposed over many years with different implications when applied to clinical practice.

This paper reviews information regarding the evolution of definitions of pain terminology and pain syndromes as they relate to everyday practice for clinicians and those operating within the medicolegal judicial system, both trainees and seasoned professionals, with a focus on chronic pain.

An historical overview of the evolution and chronology of chronic pain labels and definitions is provided with emphasis on those used currently in clinical practice.

Subsequently, the paper mainly concentrates on the two more recent revisions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and the basic principles of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) by the World Health Organization (WHO).

It further provides a summary of the newly accepted WHO ICD-11 novel classification of pain disorders, a joint effort of WHO and the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).

We conclude our review by providing our personal opinions and commentaries on controversies and dilemmas associated with the DSM, and ICD pain definitions and classifications, and offer useful tips for those who perform forensic examinations.

(emphasis and line breaks added to ease online reading)

Citation

Young, Gerald. “Thirty Complexities and Controversies in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury and Persistent Post-Concussion Syndrome: A Roadmap for Research and Practice.” Psychological Injury and Law 13, no. 4 (December 2020): 427–51.

Abstract

Mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI) is a contentious topic in the field of psychological injury and law, especially in cases in which the symptoms persist in persistent post-concussion syndrome (PPCS).

The article reviews 30 points related to MTBI/PPCS that workers in the field need to consider:

understanding these syndromes, their symptoms, their prevalence, their causation, the influences and confounds in their diagnosis, best assessment practices, and legal aspects.

valuators need to know the scientific literature, adopt an unbiased approach, undertake comprehensive assessments, consider all data and factors, and arrive at judicious decisions.

The literature indicates few conclusive findings and conclusions related to MTBI/PPCS, except for finding much variability (even in terms of definition), uncertainty, inconclusiveness, and the need for extensive research.

The literature supports the view that PPCS is biopsychosocial and that biological factors by themselves cannot account for MTBI/PPCS psychological presentations.

The psychological factors can extent into symptom exaggeration, feigning, and malingering, and these confounds need to be assessed carefully before being ruled in or out.

Ethically, evaluators should not have preconceived notions either way.

When bias is evident in these regards, the weight of testimony or proffered reports in court and related venues will be reduced or they might be deemed inadmissible.

As for recommendations, the article proposes that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), creates a new category termed somatic symptom disorder with predominant post-concussion-like symptoms.

PPCS should not be considered a syndrome or anything related to the original index concussion/MTBI and should be dropped from the lexicon in the field.

(emphasis and line breaks added to ease online reading)

Citation

Young, Gerald, William E. Foote, Patricia K. Kerig, Angela Mailis, Julie Brovko, Eileen A. Kohutis, Shawn McCall, Eleni G. Hapidou, Kathryn F. Fokas, and Jane Goodman-Delahunty. “Introducing Psychological Injury and Law.” Psychological Injury and Law 13, no. 4 (December 2020): 452–63.

Abstract

Psychology injury and law is a specialized forensic psychology field that concerns reaching legal thresholds for actionable negligent or related injuries having a psychological component, such as for posttraumatic stress disorder, chronic pain, and mild traumatic brain injury.

The presenting psychological injuries have to be related causally to the event at issue, and if pre-existing injuries, vulnerabilities, or psychopathologies are involved at baseline, they have to be exacerbated by the event at issue, or added to in unique ways such that the psychological effects of the event at issue go beyond the de minimis range.

The articles in this special issue deal with the legal aspects of cases of psychological injury, including in legal steps and procedures to follow and the causal question of whether an index event is responsible for claimed injuries.

They deal with the major psychological injuries, and others such as somatic symptom disorder and factitious disorder.

They address best practices in assessment such that testimony and reports proffered to court are probative, i.e., helping the trier of fact to arrive at judicious decisions.

The articles in the special issue review the reliable and valid tests in the field, including those that examine negative response bias, negative impression management, symptom exaggeration, feigning, and possible malingering.

The latter [malingering] should be ruled in only through the most compelling evidence in the whole file of an examinee, including test results and inconsistencies.

The court will engage in admissibility challenges when testimony, reports, opinions, conclusions, and recommendations do not meet the expected standards of being scientific, comprehensive, impartial, and having considered all the reliable data at hand.

The critical topics in the field that cut across the articles in the special issue relate to:

(a) conceptual and definitional issues,

(b) confounds and confusions,

(c) assessment and testing,

(d) feigning/malingering, and

(e) medicolegal/legal/court implications.

The articles in the special issue are reviewed in terms of these five themes.

(emphasis and line breaks added to ease online reading)

Dissociative Symptoms Associated with Greater Suicide Risk, Poor Functioning, & Co-Morbid Psychopathology

Citation

Herzog, Sarah, Brienna M. Fogle, Ilan Harpaz-Rotem, Jack Tsai, and Robert H. Pietrzak. “Dissociative Symptoms in a Nationally Representative Sample of Trauma-Exposed U.S. Military Veterans: Prevalence, Comorbidities, and Suicidality.” Journal of Affective Disorders 272 (July 2020): 138–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.177

Highlights

• 1 in 5 veterans in a broad national sample endorsed mild-to-severe dissociative symptoms.

• Vets with dissociative symptoms had greater psychiatric comorbidity and poorer functioning.

• Dissociative symptoms predicted suicide risk above other comorbidities and trauma history.

• Dissociative symptoms in veterans may be a transdiagnostic risk factor independent of PTSD.

Abstract

Background: Dissociative symptoms have been documented in diverse clinical and non-clinical populations, and are associated with poor mental health outcomes. Yet, research on dissociative symptoms is frequently limited to PTSD samples, and therefore little is known about the prevalence, clinical correlates, and risk factors related to dissociative symptoms in broader, representative trauma-exposed populations.

Methods: The current study assessed dissociative symptoms in a contemporary, nationally representative sample of trauma-exposed U.S. veterans irrespective of PTSD diagnostic status.

We then compared sociodemographic, military, and psychiatric characteristics, trauma histories, level of functioning, and quality of life in veterans with dissociative symptoms to those without dissociative symptoms; and determined the incremental association between dissociative symptoms, and suicidality, functioning, and quality of life, independent of comorbidities.

Results: A total 20.8% of U.S. veterans reported experiencing mild-to-severe dissociative symptoms.

Compared to veterans without dissociative symptoms, veterans with dissociative symptoms were younger, and more likely to be non-white, unmarried/partnered and unemployed, had lower education and income, and were more likely to have been combat-exposed and use the VA are their primary source of healthcare. They also had elevated rates of psychiatric comorbidities, lower functioning and quality of life, and a 5-fold greater likelihood of current suicidal ideation and 4-fold greater likelihood of lifetime suicide attempt history.

Limitations: Cross-sectional data limit inference of the directionality of findings, and results may not generalize to non-veteran populations.

Conclusions: Dissociative symptoms are prevalent in U.S. veterans and may be an important transdiagnostic marker of heightened risk for suicidality and psychiatric comorbidities.

These results underscore the importance of assessing, monitoring, and treating dissociative symptoms in this population.

[emphasis added; line breaks added to ease online reading]

Implications for C&P Examiners

- Enhance your understanding of dissociative symptomatology.

- Use the CAPS-5 or another well-validated structured diagnostic interview because structured or semi-structured interviews leads to more reliable and valid diagnosis and to a richer understanding of the veteran.

- In addition, the CAPS-5 has two questions about dissociative symptoms.

» These questions constituted one of the measures in this research.

- Consider administering a dissociative symptoms self-report inventory such as the Multiscale Dissociation Inventory or Dissociative Experiences Scale.

- If a veteran has dissociative symptoms, conduct a thorough suicide risk assessment.

- Have protocols in place to effectively refer suicidal veterans to a psychiatric inpatient facility, including options to have the veteran safely transported.

- Establish connections with local Veterans Health Administration (VHA) facilities—medical centers or outpatient clinics—so that you understand how to best facilitate referrals of potentially suicidal veterans. (This research article noted that the veterans with the more serious psychopathology and higher suicide risk were more likely to already be established patients at a VHA facility.)

- Assuming that you have screened and assessed for significant exaggeration/feigning, and that such dissimulation is not a concern, expect greater functional impairment with veterans exhibiting dissociative symptomatology.

- Keep in mind that standard interpretations of validity scales and symptom validity tests might need to be modified with veterans exhibiting dissociative symptomatology. For example, standard interpretation of F-scale elevations on the MMPI-2 and MMPI-2-RF must be modified, i.e., higher cutoff scores should be used.

Cause-Specific Mortality Risks Among Veterans 25 Years After 1990–1991 Gulf War

CITATION

Bullman, Tim, Aaron Schneiderman, and Erin Dursa. “Cause-Specific Mortality Risks Among U.S. Veterans: 25 Years After Their Service in the 1990-1991 Gulf War.” Annals of Epidemiology, epub before print (11 February 2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2021.01.005

ABSTRACT

Purpose: There is concern about adverse health effects related to military service in the 1990-1991 Gulf War. This study assessed cause-specific mortality risks among Veterans who served in the war.

Methods: The mortality of 621,244 veterans deployed to the Gulf War was compared to that of 745,704 Veterans who served during the war but were not deployed to the Gulf Theater. Cause-specific mortality of both deployed and non-deployed was also compared to that of the US general population.

Results: There was no increased risk of disease-specific mortality among deployed Veterans compared to non-deployed.

Deployed Veterans did have an increased risk of motor vehicle deaths compared to non-deployed Veterans, (hazard ratio, 1.12;, 95% confidence interval, 1.04-1.21).

Cause-specific mortality of both deployed and non-deployed Veterans was less than that of the US population.

When stratified by gender, only female Veterans, both deployed and non-deployed, had increased risks of suicide compared to the female US population (standardized mortality ratio, 1.40; 95% confidence interval, 1.13-1.71 and standardized mortality ratio, 1.22; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.40, respectively).

Conclusion: There was no increased risk of disease mortality among Veterans of the 1990-1991 Gulf War.

Both deployed and non-deployed female Veterans had increased risks of suicide compared to US female population.

Female and Black Veterans are Less Likely to Receive PTSD Disability Compensation

Citation

Redd, Andrew M., et al. “Exploring Disparities in Awarding VA Service-Connected Disability for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder for Active Duty Military Service Members from Recent Conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.” In "Proceedings of the 2018 Military Health System Research Symposium," edited by Patricia A. Reilly and Teresa L. Hendrickson. Supplement, Military Medicine 185, no. S1 (January-February 2020): 296–302.

Abstract

Introduction: We explore disparities in awarding post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) service-connected disability benefits (SCDB) to veterans based on gender, race/ethnicity, and misconduct separation.

Methods: Department of Defense data on service members who separated from October 1, 2001 to May 2017 were linked to Veterans Administration (VA) administrative data.

Using adjusted logistic regression models, we determined the odds of receiving a PTSD SCDB conditional on a VA diagnosis of PTSD. [If a veteran was diagnosed by a VHA clinician with PTSD, what are the odds that he or she would receive service-connected disability benefits for PTSD?]

Results: A total of 1,558,449 (79% of separating service members) had at least one encounter in VA during the study period (12% female, 4.5% misconduct separations).

Females (OR [odds ratio] 0.72) and Blacks (OR 0.93) were less likely to receive a PTSD award and were nearly equally likely to receive a PTSD diagnosis [from VHA, not the C&P exam] (OR 0.97, 1.01). [Thus, if a VHA clinician diagnosed a female veteran with PTSD, the odds that the female vet would receive service-connected disability compensation for PTSD was 0.72]

Other racial/ethnic minorities were more likely to receive an award and diagnosis, as were those with misconduct separations (award OR 1.3, diagnosis 2.17).

Conclusions: Despite being diagnosed with PTSD at similar rates to their referent categories, females and Black veterans are less likely to receive PTSD disability awards.

Other racial/ethnic minorities and those with misconduct separations were more likely to receive PTSD diagnoses and awards. Further study is merited to explore variation in awarding SCDB.

[emphasis & line breaks added to ease online reading]

Large Outpatient Psychological Dataset of Marines and Navy Personnel

Citation

Puente, Antonio E., Angela Sekely, Cuixian Chen, Yishi Wang, and Alan Steed. “Development of a Large Outpatient Psychological Dataset of Marines and Navy Personnel.” Archives of Scientific Psychology 8, no. 1 (July 2020): 15–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/arc0000074

Key Points

- This large dataset draws on extensive demographic, historical, structured interview, and psychometric information, obtained during comprehensive neuropsychological evaluations of service members referred after reporting cognitive problems.

- Evaluators administered several performance validity tests (PVTs) and symptom validity tests (SVTs).

- This initial article is descriptive in nature, although it does provide results of the Test of Memory Malingering (TOMM).

- There are of course limitations to the study, nonetheless the comprehensive nature of the evaluations and access to indices of premorbid functioning standout, along with the sheer number of "datapoints" (over one million).

Abstract

The recent wars have brought new challenges for military service members, particularly as it relates to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and blast injuries.

Though research has been conducted on the psychological effects of these injuries, the 2 most common disorders have yet to be studied together with large sample sizes. This article describes the gathering and analysis of demographic, premorbid and subsequent neuropsychological and psychological data.

The sample includes 893 active duty military personnel and has approximately 1 million data points.

We believe that this is the largest dataset of its kind and will serve as a foundation for research by both the group involved in gathering and cleaning this dataset, as well as other researchers and clinicians that request access to the data.

Scientific Abstract

The use of improvised explosive devices, rocket-propelled grenades, and landmines in recent wars has raised awareness into the effects of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

In this study, 893 active duty military personnel were administered a comprehensive evaluation that included extensive premorbid functioning e.g., Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB), structured interview, as well as psychological and neuropsychological testing postdeployment.

In this first publication on this dataset, we first present the approach taken to obtain, record, clean, and analyze the data.

Over 1 million data points are presented in a descriptive fashion to provide an initial overview of the information obtained by grouping individuals into four groups:

(a) blast only;

(b) PTSD only;

(c) comorbid blast and PTSD; and

(d) neither blast nor PTSD.

Findings using this dataset have the potential to meaningfully add to the understanding of deployment-related mTBI and PTSD.

The robustness of a demographically and psychometrically extensive dataset is discussed, as well as the inclusion of blast and PTSD groups and the value of premorbid data.

Quote re: Future Studies

... the data in Phase 1 (i.e., all profiles) were comparable with the data in phase three (i.e., valid profiles only).

This is particularly surprising as suboptimal levels of effort are predictive of decrements in neuropsychological testing.

Though future studies must be conducted to address this disparity, it could be that individuals are malingering or overreporting in one specific domain that was not identified in this preliminary analysis. Sweet (1999) explains that clinicians and researchers tend to view malingering as a dichotomous diagnostic conclusion, whereas feigning or overreporting in one domain does not imply feigning or overreporting overall.

This concept of selective presentation has been supported in the literature.

In addition, future studies using this dataset can explore this result further by assessing suboptimal effort using a multimethod assessment approach (i.e., TOMM, MMPI-2-RF validity scales, TSI validity scales).

The literature suggests that multiple assessments are needed to accurately assess effort, as the use of one effort measure alone has poor predictive validity.

A multimethod approach to assessment will determine which specific area is being feigned or exaggerated with greater predictive accuracy, thus explaining the results in Phase 3.

Addressing these results is of importance as effort may be creating a source of variance in the literature, causing disparities in research conclusions.α

Summary (Quote from Article)

In conclusion, this ongoing study contains many advantages that will enhance the understanding of postdeployment related disorders, addressing both emotional and cognitive impairment.

No inferential statistical analyses were conducted in this article, as its purpose was to describe the dataset and the methods used to gather and clean it.

With the surge of military personnel returned from OEF and OIF and the lingering effects of both PTSD and blast injuries, there is a critical and timely need to understand the emotional and neuropsychological effects of these injuries.

Future research using this dataset will build on the current understanding of the emotional and neurocognitive changes presented with combat-related PTSD and/or mTBI.

Ultimately, this research will inform servicemembers, policymakers, and clinicians about the possible emotional and neuropsychological effects of the current wars, leading to improved care.ß

Footnotes

α. Puente et al., “Development of a Large Outpatient Psychological Dataset of Marines and Navy Personnel,” Archives of Scientific Psychology 8, no. 1 (July 2020): 29.

ß. Puente et al., 31.

M-FAST Not Valid for PTSD Assessment

The article titled, "M-FAST Not Valid for PTSD Assessment" has moved to its own page.

→ M-FAST Not Valid for PTSD Assessment

Types of Malingering in PTSD

Citation

Fox, Katherine A., and John P. Vincent. "Types of Malingering in PTSD: Evidence from a Psychological Injury Paradigm." Psychological Injury and Law 13, no. 1 (March 2020): 90–104. doi:10.1007/s12207-019-09367-5

Key Points

* C&P examiners (psychologists and psychiatrists) should administer at least one, and ideally two symptom validity test (SVT) screeners and one or two performance validity test (PVT) screeners, whether or not the veteran reports serious medical problems or cognitive impairment.

* This research, along with previous studies, demonstrates that when individuals exaggerate or feign PTSD symptoms, they do so in a variety of ways, including exaggerating or feigning cognitive or physical symptoms, even if they have not suffered a physical injury such as a traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Abstract

The extent to which persons may feign or malinger psychological symptoms is an important concern for civil litigation, specifically in the context of personal injury.

The consequences inherent in personal injury cases involving psychological distress require an understanding of how malingering presents in medico-legal contexts, and how it can be assessed using available measures.

Symptom validity tests (SVTs) and performance validity tests (PVTs) have been developed to assist in the detection of feigned psychological illness and neurocognitive impairment.

While demonstrated divergence between symptom-based and performance-based outcomes have been demonstrated in civil litigants with posttraumatic symptoms after the experience of a physical injury, limited research has evaluated how these measures operate in the context of psychological injury alone.

The present study evaluated the relationships among symptom-based and performance-based measures of malingering under a simulated personal injury paradigm in which psychological but not physical injury was sustained.

A total of 411 undergraduate participants completed four measures of malingered symptomatology, including both symptom validity and performance validity indicators. Participants were instructed to respond to measures as if they were experiencing common emotional, behavioral, and cognitive symptoms of PTSD following a motor vehicle accident.

Using a multi-trait multi-method matrix, weaker correlations were found between PVT and SVTs (ranging from .15 to .28), but moderate significant correlations were found across symptom validity measures (.51 to .65), thus demonstrating an expected dissociation between methods of malingering assessment.

Additional analyses support the stability of these findings, when accounting for past exposure to motor vehicle accidents, and replicated the need for a multiple failure approach.

Findings are consistent with expectations of convergent and discriminant validity and support the conceptualization of malingered PTSD as a non-unitary construct that is composed of multiple domains or “types,” as reflected by a lack of convergence between SVT and PVT methods.

In practice, evaluators of psychological injury are encouraged to utilize more than one measure of malingering, including both PVT and SVT approaches, when PTSD is alleged.

(Paragraph breaks, bold text, and emphasis added to facilitate online reading.)

What is the Best PAI Validity Scale for PTSD Exams?

Note: See also New PAI Plus on the C&P Exam News page.

Citation

Russell, Duncan N., and Leslie C. Morey. "Use of Validity Indicators on the Personality Assessment Inventory to Detect Feigning of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder." Psychological Injury and Law 12, no. 3–4 (2019). doi:10.1007/s12207-019-09349-7

Key Points

The Multiscale Feigning Inventory (MFI)α was the best (most effective) PAI validity scale for detecting feigned PTSD.

The MFI had the largest effect size; best combination of sensitivity and specificity; and it demonstrated incremental validity over the NIM (Negative Impression Management) scale.

- Largest effect size (Cohen's d = 1.37)

- Sensitivity = 59.1 / Specificity = 92.0 (at cutoff: > 81.0)

- Incremental validity (ηp2 = .285, p < .01)

The Hong Malingering Function, developed by Korean researchers,ß also demonstrated incremental validity over the NIM scale, and showed moderate sensitivity to feigned PTSD with specificity over 90%.

Abstract

This study examined the ability of several Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI) validity indicators to detect feigning of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Participants included 491 individuals recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTURK): 44 participants were asked to feign PTSD, 25 participants carried a diagnosis of PTSD and demonstrated at least moderate levels of current symptoms, and 422 served as control subjects.

Results indicated that all of the PAI negative distortion validity indicators significantly distinguished the true PTSD from the feigned PTSD group.

The indicators with the largest effect sizes were the Hong Malingering Function and the Multiscale Feigning Index, both of which demonstrated moderate sensitivity to feigned PTSD with specificity above 90%.

Footnotes

α. Gaines, Michelle V., Charles L. Giles, and Robert D. Morgan. “The Detection of Feigning Using Multiple PAI Scale Elevations: A New Index.” Assessment 20, no. 4 (2013): 437–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191112458146 | Google Scholar

ß. Hong, S. H., and Y. H. Kim. "Detection of Random Response and Impression Management in the PAI: II. Detection Indices." Korean Journal of Clinical Psychology 20 (2001): 751–761.

MMPI-2-RF: Identifying UNDER-reporting

Citation

Brown, Tiffany A., and Martin Sellbom. The Utility of the MMPI–2–RF Validity Scales in Detecting Underreporting. Journal of Personality Assessment 102, no. 1 (2020): 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2018.1539003

Abstract

This study examined the [underreporting] validity [scales] of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory–2–Restructured Form (MMPI–2–RF):

- Uncommon Virtues (L-r)

- Adjustment Validity (K-r)

The study aimed to increment the previous literature in this field using a New Zealand population. We used a combined sample of 784 university students, with 173 participants completing the MMPI–2–RF with instruction to underreport in the context of applying for a job, and 611 completing the test under standard instructions.

Results indicated that individuals who completed the MMPI–2–RF with underreporting instructions exhibited significantly lower scores on the majority of the MMPI–2–RF substantive scales, and significantly higher scores on the L-r and K-r validity scales.

Additionally, L-r and K-r added incremental predictive utility over one another when differentiating the standard instruction and underreporting groups.

Classification accuracy analyses provided additional evidence for the utility of the L-r and K-r scales by supporting their respective cut scores listed in the MMPI–2–RF manual.

The findings of this study provide further evidence for the utility of the L-r and K-r scales in detecting underreporting extension to both a preemployment evaluation context and a novel population.

Comment

It is not uncommon for veterans to under-report psychological problems and symptoms during Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) disability exams for PTSD and other mental disorders.

This is another reason why VA psychologist-examiners should administer a multiscale inventory like the MMPI-2-RF during VA claim exams.

With encouragement, many veterans who underreport problems will discuss the actual severity of their symptoms and associated functional impairment.

But if you don't know that a veteran is underreporting, you are more likely to accept their self-reported problems at face value.

A veteran's increased openness leads to a more accurate disability rating and improved receptiveness to mental health counseling or psychiatric care.

Corresponding Author

Martin Sellbom PhD

Department of Psychology

University of Otago

Dunedin, New Zealand

Image by Ulrich Lange, Dunedin, New Zealand

Image by Ulrich Lange, Dunedin, New Zealand

Losing Service Connection for

PTSD is Uncommon

Citation

Murdoch, Maureen, Shannon Kehle-Forbes, Michele Spoont, Nina A Sayer, Siamak Noorbaloochi, and Paul Arbisi. Changes in Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Service Connection Among Veterans Under Age 55: An 18-Year Ecological Cohort Study. Military Medicine 184, no. 11-12 (Nov-Dec 2019): 715–722. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usz052

Corresponding Author

Maureen Murdoch MD MPH

Center for Care Delivery and Outcomes Research

Minneapolis VA Health Care System

One Veterans Drive (152)

Minneapolis MN 55417

Abstract

Introduction

Mandatory, age-based re-evaluations for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) service connection contribute substantially to the Veterans Benefits Administration’s work load, accounting for almost 43% of the 168,013 assessments for PTSD disability done in Fiscal Year 2017 alone. The impact of these re-evaluations on Veterans’ disability benefits has not been described.

Materials and Methods

The study is an 18-year, ecological, ambispective cohort of 620 men and 970 women receiving Department of Veterans Affairs PTSD disability benefits.

Veterans were representatively sampled within gender; all were eligible for PTSD disability re-evaluations at least once because of age.

Outcomes included the percentage whose PTSD service connection was discontinued, reduced, re-instated, or restored. We also examined total disability ratings among those with discontinued or reduced PTSD service connection.

Subgroup analyses examined potential predictors of discontinued PTSD service connection, including service era, race/ethnicity, trauma exposure type, and chart diagnoses of PTSD or serious mental illness.

Our institution’s Internal Review Board reviewed and approved the study.

Results

Over the 18 years, 32 (5.2%) men and 180 (18.6%) women had their PTSD service connection discontinued; among them, the reinstatement rate was 50% for men and 34.3% for women.

Six men (1%) and 23 (2.4%) women had their PTSD disability ratings reduced; ratings were restored for 50.0% of men and 57.1% of women.

Overall, Veterans who lost their PTSD service connection tended to maintain or increase their total disability rating.

Predictors of discontinued PTSD service connection for men were service after the Vietnam Conflict and not having a Veterans Health Administration chart diagnosis of PTSD; for women, predictors were African American or black race, Hispanic ethnicity, no combat or military sexual assault history, no chart diagnosis of PTSD, and persistent serious mental illness.

However, compared to other women who lost their PTSD service connection, African American and Hispanic women, women with no combat or military sexual assault history, and women with persistent serious illness had higher mean total disability ratings.

For both men and women who lost their PTSD service connection, those without a PTSD chart diagnosis had lower mean total disability ratings than did their counterparts.

Conclusions

Particularly for men, discontinuing or reducing PTSD service connection in this cohort was rare and often reversed.

Regardless of gender, most Veterans with discontinued PTSD service connection did not experience reductions in their overall, total disability rating.

Cost-benefit analyses could help determine if mandated, age-based re-evaluations of PTSD service connection are cost-effective.

Key Points

Important points about the research article, Changes in Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Service Connection Among Veterans Under Age 55: An 18-Year Ecological Cohort Study:

(1) For men, mandatory review exams for PTSD rarely result in reduced or discontinued service-connected disability benefits.

- 2.6% of men had their PTSD service connection discontinued (after appeals).

- 0.5% of men had their PTSD service connection rating reduced (after appeals).

(2a) For women, mandatory review exams for PTSD sometimes result in discontinued service-connected disability benefits.

- 12.2% of women had their PTSD service connection discontinued (after appeals).

(2b) For women, mandatory review exams for PTSD rarely result in reduced service-connected disability benefits.

- 1.0% of women had their PTSD service connection rating reduced (after appeals).

(2c) C&P examiners might harbor implicit biases against African-American and Hispanic women. [That is my conclusion, and does not necessarily reflect the authors' opinion. - Dr. Worthen]

(3) If the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) does reduce or discontinue a veteran's service-connected disability compensation for PTSD, he or she has a decent chance of the decision being reversed upon appeal.

(4a) For both men and women, those without a VHA PTSD chart diagnosis were more likely to lose their service connection for PTSD, and they had lower mean total disability ratings than did their counterparts.

(4b) Implication for veterans: If you received PTSD treatment at a Vet Center or from a non-VA mental health clinician, make sure to obtain and include those records with your PTSD disability compensation claim.

IMPORTANT Info about Vet Center Records

Vet Center records must be requested directly from the Vet Center where you received counseling.

⇒ You will not receive Vet Center records when you request your medical records from a VA medical center's Release of Information (ROI) Office.

⇒ Your Vet Center records are not on My HealtheVet.

⇒ The Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) does not routinely seek out Vet Center records because most veterans have not been to a Vet Center. However, a lot of veterans with PTSD have sought counseling a Vet Center, and those Vet Center records could prove very helpful to your claim.

Use the Vet Center locator to find contact information for any Vet Center(s) where you have received counseling.

Call the Vet Center for advice on how to best obtain your records. For example, if you live close enough, it might be faster to simply visit the Vet Center. Otherwise, mail VA Form 10-5345a to the Vet Center to request your records.

Older Articles: Table of Contents

- Detailed Assessment of Posttraumatic Stress–Second Edition (DAPS-2)

- WHODAS 2.0 & PTSD Disability Assessment

- MMPI-2-RF Validity Scale Scores Across VA Medical Centers & Clinics

- Mild TBI Assessment: MoCA Validity

- Forensic Perspective on Disability Evaluations

- Moral Injury: an Integrative Review

- Disability Examinations Require Forensic Psychology Competence

Detailed Assessment of Posttraumatic Stress–Second Edition (DAPS-2)

Citation